Conflict in Bed

Conflict is the opposition or confrontation between individuals or groups who are in disagreement. When someone or something jeopardizes our interests, we enter into conflict and try to minimize potential harm. Conflicts come in various forms: social, linguistic, war-related, political, and… even sexual. Sexual conflict arises when both sexes have reproductive strategies that reduce the fitness (or reproductive success) of the opposite sex, usually based on the manner or frequency of copulation. The conflict between sexes can lead to a process known as antagonistic sexual coevolution. This is when structures and behaviors enhance the fitness of one sex but harm the opposite sex. The other sex typically evolves structures and behaviors over generations to defend itself. This process ultimately results in the development of exaggerated and opposing sexual structures.

In other words, as the sword sharpens, it’s an advantage for the shield to fortify, resulting in the need for an even sharper sword. Over time, the sword is likely to become exceedingly sharp, and the shield remarkably thick.

Bedbugs are an example of sexual conflict, as the male’s best reproductive strategy is fatally damaging to the female. They reproduce through traumatic insemination, meaning that males do not penetrate female genitals, but instead, pierce their needle-like penis into the females’ abdomen, causing injury. Usually, sperm is injected directly into the hemolymph (equivalent to our blood) and travels to organs that store it until needed to inseminate eggs. Since the sperm from the last mating male has the highest probability of fertilizing the eggs, the male is highly motivated to have multiple copulations. If it reproduces frequently and with many females, it has a higher chance of fertilizing some eggs. This is where the conflict arises. It benefits the male to copulate frequently, but for the female, who suffers an injury with each mating, it ends up being extremely dangerous.

This reproductive strategy imposes significant costs on the female. High copulation frequencies do not increase fertility; instead, they decrease her longevity, either due to intestinal perforation or secondary infections.

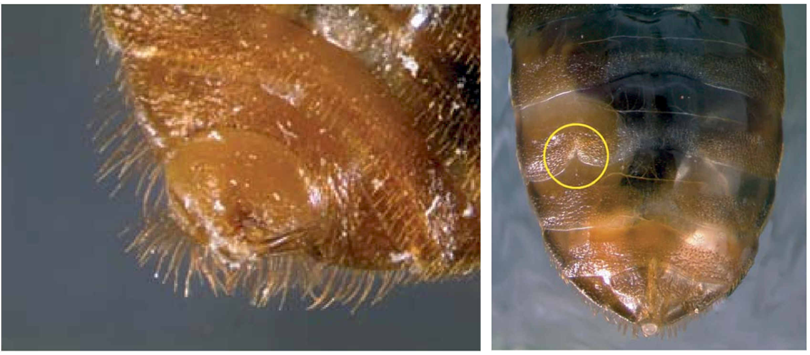

In some species, females have developed structural and behavioral adaptations to mitigate these costs. The structural adaptation is the spermalege, a structure that divides into ectospermalege and mesospermalege. The ectospermalege is a hard layer of keratin in a specific area of the abdomen where the male penetrates with his penis. The mesospermalege is just below, inside the body, and is a spherical pouch that receives, filters, and conducts the injected sperm to the hemolymph. This way, the wound is focused on a single point, and the sperm reaches the bloodstream indirectly, reducing the risk of infection.

The behavioral adaptation in females involves migrating from the bedbug group after the initial copulations to go to untouched areas or spots where only female groups are found. This way, they avoid further injuries to the abdomen and also colonize new habitats with less competition for resources.

For female bedbugs, the pressure from males has been crucial in developing these structures and behaviors. Despite both sexes having the same purpose—passing on their genes to offspring—they have an antagonistic relationship during copulation, turning an act as natural as sex into a struggle.

REFERENCE

Kamimura, Y., Mitsumoto, H., & Lee, C. (2014). Duplicated Female Receptacle Organs for Traumatic Insemination in the Tropical Bed Bug Cimex hemipterus : Adaptive Variation or Malformation ? PLoS ONE, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089265

Morrow, E. H. (2003). Costly traumatic insemination and a female counter-adaptation in bed bugs. THE ROYAL SOCIETY, (April), 2377–2381. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2003.2514

Pfiester, M., Koehler, P. G., & Pereira, R. M. (2009). Traumatic Insemination in Bed Bugs. American Entomologist, (May 2014). https://doi.org/10.1093/ae/55.4.244

Stutt, A. D., & Siva-jothy, M. T. (2001). Traumatic insemination and sexual conflict in the bed bug Cimex lectularius. Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield., 98(10).